This article is part of our “Psychology of a Pandemic” series.

In his 1990 essay published in Sociology of Health & Illness, sociologist Philip M. Strong wrote:

“A major outbreak of novel, fatal epidemic disease can quickly be followed both by plagues of fear, panic, suspicion and stigma; and by mass outbreaks of moral controversy, of potential solutions and of personal conversion to the many different causes which spring up. This distinctive collective social psychology has its own epidemic form, can be activated by other crises besides those of disease and is rooted in the fundamental properties of language and human interaction.”

Fast forward to thirty years later: The spread of SARS-CoV-2—and the lethal, highly contagious disease it causes, COVID-19—prompted countries across the world to adopt drastic containment and mitigation measures.

In the Philippines, the spirit of bayanihan burns brightly. Both the private and public sectors have gone above and beyond to address issues, inadequacies, and inconsistencies in the national government’s overall response to this health crisis.

Unfortunately, our present circumstances appear to have brought out not just the best, but also the worst in us.

A creeping sense of dread

As of this publishing, the entire island of Luzon is under an enhanced community quarantine that is expected to last until mid-April.

“At its most basic, [the quarantine] is a departure from everyday life as we know it,” explains Dr. Trina de la Llana, a consultation-liaison psychiatrist. “We don’t know when it will end, or what’s in store for us in the coming weeks.”

According to de la Llana, it’s the unpredictability and the restriction of movement that have made people feel uneasy. However, what makes the situation worse is the thought that we were caught off guard.

“It’s knowing that drastic actions were taken in order to prevent infection by an unseen enemy that could already have breached your defenses,” says de la Llana.

“It’s the mute fear that you could already be infected, but test kits are few.”

The panicking Pinoy

COVID-19 has also changed consumer behavior in the blink of an eye. In fact, local government units have put specific measures in place to prohibit panic-buying.

“Panic-buying is a reflection of the uncertainty of these days, fed by social media rumors, the fake news mill, and very long announcements on the news with detailed instructions that aren’t always easy to understand or remember,” says de la Llana.

At a time like this, it’s admittedly easy to fall into the trap of panic-buying. Sure, you may have entered the store with a list of things to buy. As soon as anxiety sets in, though, your mindset shifts from buyer to hoarder. And when other people observe you behaving this way, they’re likely to follow suit.

Inevitably, the resulting shortage of food, protective gear, and other basic necessities will endanger everyone. That’s because the members of the community without access to sustenance or protection become especially vulnerable to the coronavirus. And if enough of them get sick, you become more susceptible, too.

Worse, the sudden, lopsided balance between supply and demand would send prices skyrocketing. This, of course, increases the difficulty of obtaining even the most basic of necessities.

Basically, hoarding all the toilet paper or corned beef in your town is a terrible idea.

“While preparing is rational,” de la Llana asks, “how much of something does your home need, realistically?”

Miracle cures and misinformation

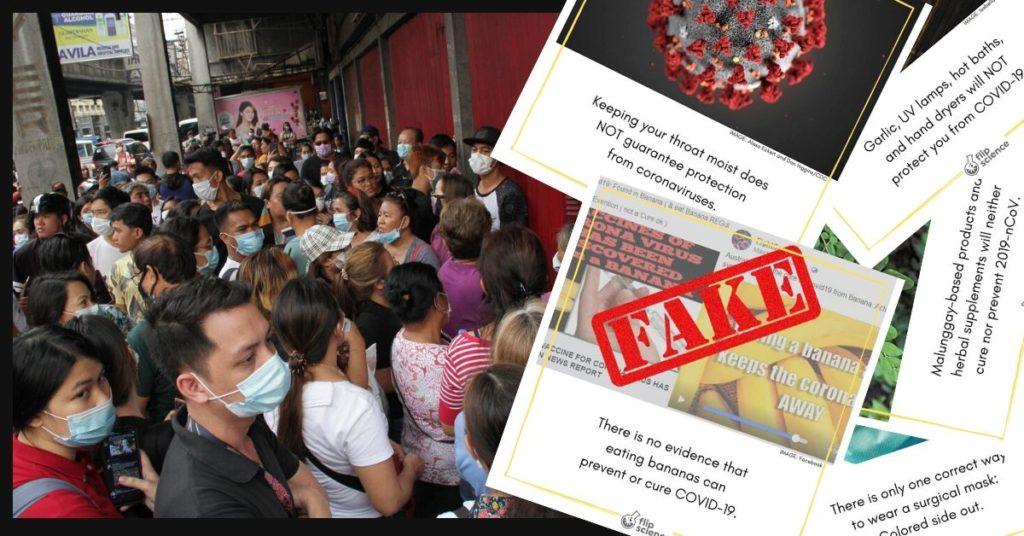

In addition, we’ve also seen a surge in misleading news and misinformation about COVID-19 online. Countless online users (and opportunistic sellers) have shared bogus claims that warm water, garlic, bananas, and even ‘green zone’ amulets can stop the coronavirus.

Unfortunately, those of us who are quick to believe unverified claims or desperate for any sort of update are easy pickings for clickbait titles, catchy videos, and fabricated “advice” from fictitious “experts.”

Others seem to revel in sharing conspiracy theories and unconfirmed reports that portray the situation in a much darker light. This may be a manifestation of confirmation bias. “Since they have a negative view of the situation, there is a greater tendency to gravitate towards (and share) these negative news items.”

When emotions are high—or as de la Llana puts it, when being able to “do something to help” is of paramount importance—we end up clicking before we think.

“A lot of things are done with the best of intentions—but can lead to horrible consequences.”

The harm in both extremes

So, is it okay to be anxious and panicky? Or is it better to stay calm and pretend that everything’s normal?

Unfortunately, the answer isn’t quite that simple.

“Both might not follow guidelines set by experts in order to keep the public safe, and could contribute to the spread of the virus,” explains de la Llana.

“Both behaviors lend themselves to not taking others into consideration, and can have bad effects on public health.”

Ultimately, how we respond to the pandemic depends on our personalities, our previous experiences, and how we perceive the world. To stay anchored and rational, perhaps we should remind ourselves that no deed, good or bad, goes unpunished—especially at a time like this.

Cover photo: Gil Calinga/Philippine News Agency

References

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/1467-9566.ep11347150

- https://www.discovermagazine.com/health/why-coronavirus-is-turning-people-into-hoarders-a-q-and-a-on-the-psychology

- https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/how-should-clinicians-integrate-mental-health-epidemic-responses/2020-01

- https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/psychiatrists-beware-impact-coronavirus-pandemics-mental-health/page/0/1

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/talking-about-health/202003/mental-health-in-time-pandemic

Author: Mikael Angelo Francisco

Bitten by the science writing bug, Mikael has years of writing and editorial experience under his belt. As the editor-in-chief of FlipScience, Mikael has sworn to help make science more fun and interesting for geeky readers and casual audiences alike.