Note: This piece was first published on Rappler.

“COVID-19 DEFEATED”

Imagine seeing this in the headlines, maybe 3 or 4 months from now. We can travel anywhere, get toilet paper in stores, and even meet our dates, friends, and loved ones again. Things will be back to normal, the way they used to be…

Except they won’t. COVID-19 has forever changed our normal, whether we like it or not.

The coronavirus pandemic has caused so many things to transpire: some predictable, most not. Who’d have thought that the very first “global event” to come out of it would be a toilet paper stockout? There were even “toilet paper calculators” popping up online last March! (True story: I found at least three working websites dedicated to calculating your TP usage for the month.)

One more surprising development for me was getting the opportunity to work with medical professionals. I became a part of a collaborative community of technologists committed to providing solutions for COVID-19 and its fallout.

Mind you, I am no frontliner, not a nurse nor a medical doctor. In the fight against the coronavirus, I serve as an engineer/designer in one of the country’s biggest universities. I assist and provide basic support to those on the frontlines, so they can perform their heroic jobs safely and without any worry.

A backliner’s journey

As non-essential personnel in the first weeks of the pandemic, my thoughts were the same as everybody else: “Where the hell do I get toilet paper?”

I didn’t have a lot of selfless and noble ideas back then to fight the virus. I was more concerned about my trips being cancelled and Black Widow being rescheduled to November instead of May this year.

Admittedly, I had brushed off COVID-19’s threat, thinking that I wouldn’t even have anything to contribute not being in the medical field. Obviously, I was very wrong.

As the weeks went by under Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ), the number of COVID-19 cases steadily climbed. The government continued to roll out cash assistance programs and national policies to combat the pandemic and its consequent tragedies. Implementation, however, was a different matter altogether.

As lapses in the execution of these policies became evident, the public grew restless. Soon enough, hospitals cried over the lack of necessary Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), public transport drivers begged for work, and small business owners filed for bankruptcy. Complaints came forth, creating an online ruckus about the crisis mismanagement and unjust decrees that bared latent interclass tensions within Philippine society.

Soon after, fear of hunger overwhelmed fear of the disease, and the public took the streets. Seeing how the pandemic has brought the country to the brink of disorder, many private citizens were forced to mobilize and assist in any way possible. Makers, designers, engineers, students, artists, carpenters, craftsmen, weavers, and more joined the fight and entered the pandemic ring. These non-medical practitioners constitute the country’s COVID-19 “backliners.”

Collaboration is the cure

My backliner journey started with a simple design, a face shield frame. I collaborated with my University’s College of Fine Arts to make face shield frame designs that could easily be 3D printed and laser-cut. The initial prototype was given out to medical professionals and other frontliners with a simple request: that they provide us with feedback, so we could continuously improve the product to better suit their needs. In total, the team was able to make and distribute 1,500 face shield frames to small hospitals and local government units around the Philippines.

Later, I was fortunate and blessed to be able to join the UP Manila’s Surgical Innovation and Biotechnology Laboratory (SIBOL) team of tech professionals, brought together to collaborate for solutions against the “invisible enemy.” It is basically a think tank composed of big names in the research industry, brought together by Dr. Edward Wang. However, in the eyes of a young professional like me, it pretty much looked like the Avengers (or the Justice League, if you’re a DC fan). I can still vividly remember our first Zoom meeting. There, on my screen, were the leading researchers in various science and engineering fields in the country. I sat in my room facing my laptop, in awe! (Sucks that I couldn’t meet them in person to fanboy, but considering the circumstances, it’s definitely for the best).

Working and exchanging ideas with these multidisciplinary experts was really exhilarating. But the in-depth discussions and quick hurling and tossing of propositions could make one lose track of what’s happening, especially given the complexities of remote communication (which we were forced to adopt, given the state of affairs). Personally, I believe this is one of the main challenges of ideation in the pandemic setting. As a product design teacher, I always tell my class that design sprints with the potential user or target market need to be personal and intimate. This allows the designer to get as much information as possible from the client, including the nonverbal ones. Online meetings and interactions are also prone to miscommunication, which could easily wreck the brainstorming process.

But how do we make online ideation intimate and personal? How do we transcend the virtual borders and create a useful designer-client connection?

Here’s what I found out: Given the limitations of the type of communication, it is important to compromise a little bit on the designer-client idea exchange and focus on one-way idea transfer. What this means is full reliance on the experience and knowledge of the medical professionals regarding what they need and fully letting go of that tenacious engineering/design trait known as the “hero complex.”

Don’t be a hero

Most engineers and designers suffer from what is known as the hero syndrome. They go marching into places with real-life technical challenges like rural communities, small hospitals, and barrio schools with chest puffed out exclaiming, “We’re engineers from *insert random University/College* and we’re here to solve your problem for you!” This is exactly how it goes for most engineering projects I know, true story.

But here’s the thing: a three-day immersion will never match the years of experience locals and residents have. They face those challenges every day, so they probably know the most fitting solution, a fix that can easily be adopted given their culture and condition. The biggest insult you can throw their way is to take the helm and steer their boat. Quite possibly, they simply lack the capability to shape up their ideas into an actual product/process. What they need is someone who can realize their solutions, someone who can listen and retell their story.

The same applies when engineering or designing for healthcare. As a backliner, it would be detrimental to the communication and design process for us engineers to take the lead, even more so given the non-ideal online setup of the design sprint. Our limited knowledge and experience with medical processes and culture would have prevented us from making appropriate solutions. Listening to the doctor’s needs became key. Essentially, the entire design process is just a retelling of their story and a strengthening of their narrative.

Designing for care is designing for diversity

As some of the projects proposed started rolling out, I discovered that healthcare engineering means considering diversity and inclusion without exception.

As our team designed and fabricated the “Sanipod: Self-contained Disinfecting Cubicle” alpha prototype, we went through a few (a lot, really) of revisions, particularly on the height and width of the cubicle and the positioning of the spray nozzles. This is actually nothing new; after all, design is an iterative process. But as I became exceptionally frustrated re-drilling holes and re-positioning the piping system, I began to realize what we were missing.

We were always thinking of the AVERAGE. We asked questions like “What is the average height of Filipino males and females? What is the average width of the potential users?” Now, there’s nothing wrong about this per se. Truth be told, all engineering and design classes will teach you to always consider the standard user when developing a product.

However, medical products are on an entirely different level. It’s not about accessibility for most, it’s about accessibility for all.

If we had designed the Sanipod based on the standard, those with proportions at the extremes would never be able to fit in there. The medical professionals I worked with, Dr. Cathy Co and Dr. Edward Wang, made me realize how limiting my design thinking was. They showed me a whole new way of designing for diversity and inclusion.

Move slow and DO NOT break things

Being a product developer, it is important to move quickly, as new products get created every day. I also teach my students that at the initial phase of the ideation process, quantity is more important than quality. “More is always better,” as I always advise my class. I even try my hardest to make the classroom as accepting of mistakes and bad designs as possible. This way, they’d be able to easily identify the best among the rest. In our classes, we live by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg’s now-famous motto, “Move fast and break things.” Innovate as fast as possible, welcome mistakes, and grow rapidly by taking risks.

This design motto does not apply to the healthcare industry, though. In contrast, it does not allow you to take risks when inventing and innovating. Why? Because in the medical industry, it is always a matter of life and death.

Everything, even the smallest details, must be carefully thought of. This includes how the product can be integrated into hospital operations before releasing it. Believe it or not, our alpha prototypes were already functional and ready for deployment given the cautious scrutiny of the medical professionals we worked with.

This way, I learned that there’s no such thing as “too much care” in healthcare.

The need for speed

Healthcare providers need to be agile and quick when attending to a patient. During emergencies, their pace dictates life or death. “Who lives? Who dies?” is not a question a medical professional should be wasting his/her precious time answering. This dilemma now becomes the driving force for hospitals evolving to become more mobile and portable.

The same goes for designing medical devices. When our team was working with Dr. Cathy Co for her idea on a Laryngoscope disinfection device, we tried, at first, to integrate the various disinfection techniques into one holistic product. We wanted to include as many features in the device as possible, to make it more beneficial. Needless to say, the first design I submitted was as big as an industrial washing machine!

Upon seeing the design draft, Doc Co made recommendations focusing on making the equipment lighter and more mobile, as doctors might need to move it around the hospital as quickly as possible. Honestly, I never considered size and weight implications on medical professionals during the design stage. I was primarily focused on how to integrate all the subsystems and features desired. The more, the better, right? Obviously, I was wrong, again.

When Doc Co suggested dropping some optional features to make the device smaller and lighter, I realized that mobility should be the top priority. With the right mindset, the team then designed a laryngoscope disinfection device the size of a toolbox. 😉

Up close and personal

We can hold online meetings as much as we want, watch online presentations, and maybe attend seminars on medical equipment, but those can never compete with real-life interaction.

Design is fundamentally about spending time with the real users. That’s how we obtain immense amounts of texture and richness about how the product and experience are going to take shape. So, I came up with this rule: immerse, interact, and have fun doing so.

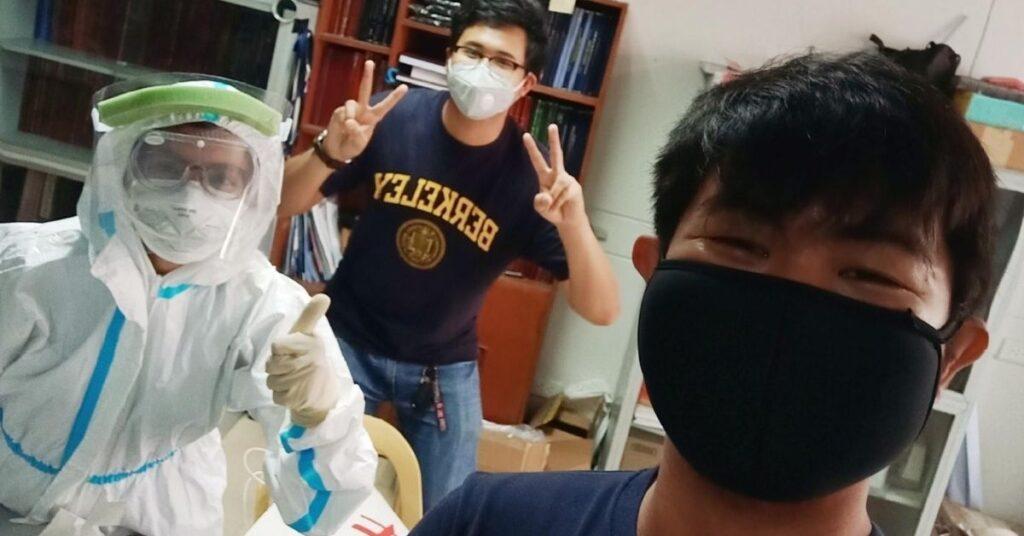

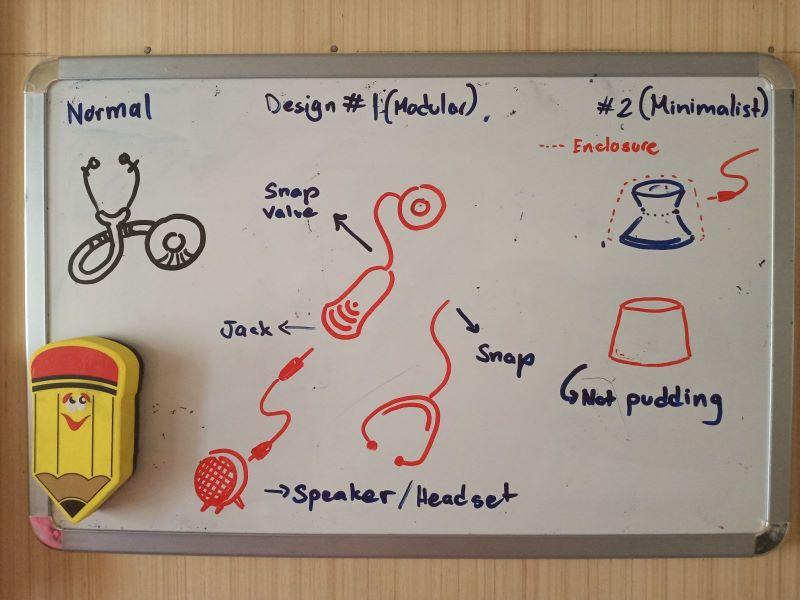

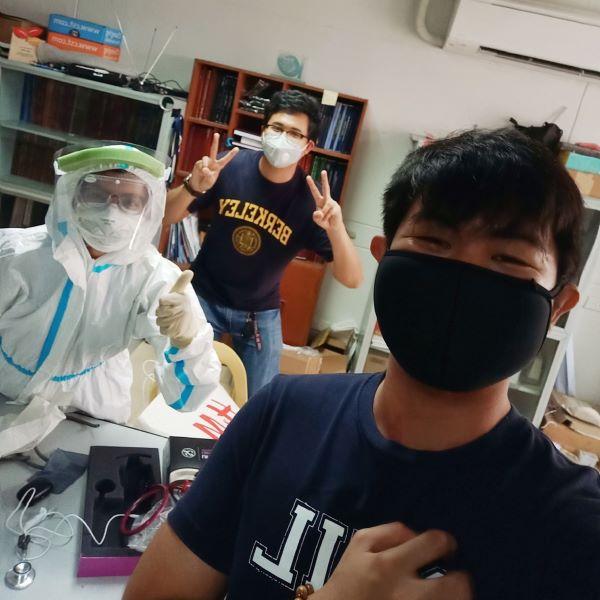

When we were designing Doc Mikki Miranda’s digital stethoscope, we had to meet her in person. She wanted to show us the difficulties of using a conventional stethoscope with full PPE on. My close friend Engr. Charleston Ambatali, who worked on the circuitry and electricals of the device, organized a safe meeting setup for all of us. She taught us how to use a stethoscope, and showed us its basic parts. Doc Mikki also donned her full PPE for display.

And since we wouldn’t miss a chance to capture a moment, here’s a snap of us from that time.

I was also able to wear a full PPE when we were testing the Sanipod system prior to deployment in PGH. It was an amazing experience—but boy, it was hot under all those layers! I don’t even know how our doctors wear those for hours. Here’s a picture of me slaying in my brightly colored coverall and face mask.

Finally, working with all these amazing people under the SIBOL team has taught me that designing for healthcare is more demanding than any other sector and industry I’ve had previous experience in.

A designer or engineer looking towards a career in the medical industry must charge head-on with an open mind and an optimistic attitude. Recognize that the stakes are always higher—and the potential outcomes, even more so.—MF