By Frances Mae Tenorio

Humans and cats have had a long-standing connection since time immemorial. Across millennia, cat domestication has turned the furry felines into pest control machines and even beloved companions to humans. However, this mutually beneficial relationship also has its dark side.

In the Philippines, for instance, cats are among the most popular household pets. Sadly, the country also has a high population of unwanted cats, said to be in the millions. They prowl the streets, scavenging for food and shelter. In many cases, they end up as roadkill.

But what happens to domesticated cats that live in close proximity to — or survive long enough to roam freely in — the wild?

Uncontrolled cat predation and biodiversity loss

Over the centuries, as human settlements increased, cat populations also grew, paving the way for a decline in native faunal populations. Based on research from different parts of the world, the presence of cats in certain habitats has been the catalyst for various species extinctions.

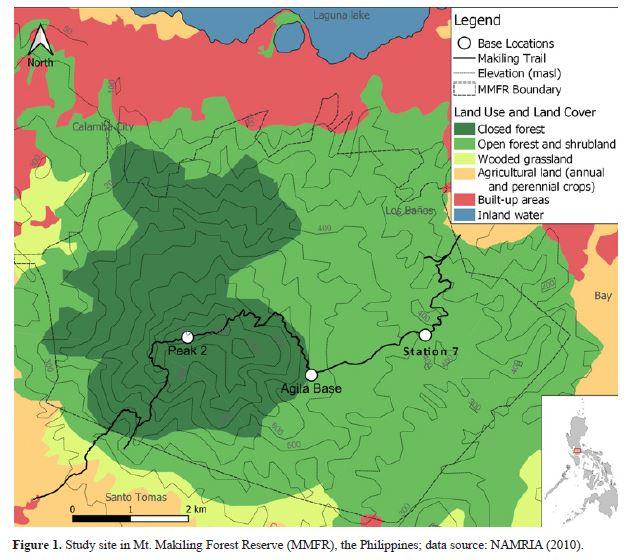

To better understand this phenomenon in the Philippines, a team of researchers led by MS Wildlife Studies graduate Frances Mae Tenorio studied the behavior of domestic cats (5 male and 1 female) owned by residents living within the Mt. Makiling Forest Reserve. They attached GPS collars to the cats and tracked the felines’ movements for 7 days every month for a period of 5 months. Additionally, they recorded the prey items that the cats took home to determine their predation return rate.

Results showed that the cats roamed extensively, having an average home range (defined by the researchers as “the area where an animal conducts its daily activities such as foraging, mating, and caring for the young”) between 51 and 81 hectares. Moreover, the male cats in the study were observed to have larger home ranges than the female cat. This is consistent with international findings about domestic cat home ranges. Prey items that the cats typically brought home include lizards (e.g., skinks and monitor lizards), rats, and bats.

According to Tenorio, “Though the predation return rate is small (1.1 prey per month for all cats), the effects of cat predation on our wildlife may be severely underestimated. Cats may kill wildlife and eat them without taking them home, or simply kill wildlife for fun.”

The team published their findings in the Philippine Journal of Science in February 2024.

Possible solutions to domestic cat predation

Numerous cat studies show that domestic, stray, and feral cats can have a severe negative impact on wildlife, ranging from predation to the spread of zoonotic diseases.

Currently, there are no Philippine laws to specifically reduce the impact of cats on wildlife. Per Tenorio’s team, domesticated cats in protected areas should be registered, sterilized, vaccinated, and always kept indoors, if not prohibited from entering wildlife habitats. Sterilization or castration helps in both reducing stray animal populations and increasing cats’ life expectancy. As for stray cats, management strategies may include capture, castration, vaccination, and transfer to animal shelters for adoption.

Lastly, proper communication and education campaigns involving cat owners and their communities are crucial for the effective implementation of conservation strategies involving domestic cats. —MF

About the Author: Frances Mae Tenorio MSc, is currently a DOST Career Incentive Program fellow at the UPLB Museum of Natural History under DOST-Science Education Institute. She is a wildlife biologist by degree and an artist by heart.