Inside a small, stuffy cave in Batangas, researchers found a species of spider that has never been recorded in the Philippines before—a discovery with potential impacts on environmental policy and local tourism.

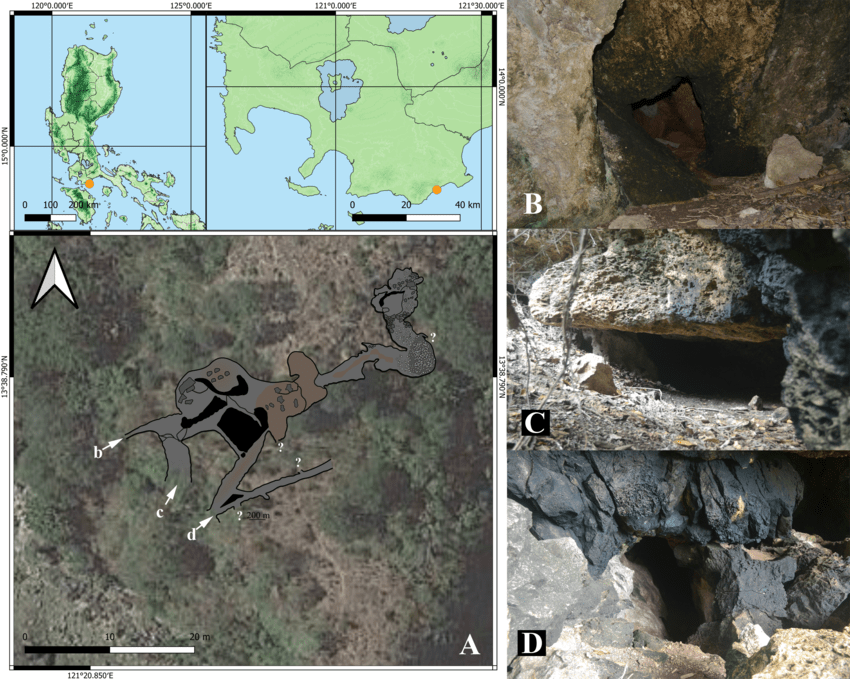

A stone’s throw away from the southeastern shoreline of Lobo, Batangas, is a small cave called Kamantigue. Nearly everything about it—a tiny opening that a person can only fit through by crouching, ample deposits of guano in its dry crevices, the looming possibility of death from above via collapsing rocks—suggests that nature designed it specifically to repel visitors. Yet strangely enough, beachgoers seem to feel compelled to enter this unwelcoming chamber (as evidenced, rather embarrassingly, by the food wrappers, plastic bottles, and other types of litter they keep leaving behind).

But not all who enter this cave of hazards do so out of a misguided sense of adventure. In September 2022, as part of Project 3 of the Niche Centers in the Regions for Research and Development-Center for Assessment of Cave Ecosystems (NICER-CAVES) Program, Dr. Aimee Lynn Barrion-Dupo and her team of terrestrial arthropod researchers crawled their way into Kamantigue Cave, which was included in their sampling area in the CALABARZON region.

“We felt that the cave wasn’t all that exciting, because there were so many cockroaches inside,” shared Barrion-Dupo, an arachnologist and professor at the University of the Philippines Los Baños (UPLB). She also observed that, oddly enough, there were no huntsman spiders or tarantulas there, which are typical roach predators. “We just really wanted to get out of that cave.”

The abundance of Periplaneta americana roaches in the cave was far from their only challenge, though. At the time, the Philippines was still officially under a state of public health emergency due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the researchers had to keep their facemasks on, enduring the uncomfortable temperature and stuffy air inside the cave while patiently collecting spider and arthropod specimens. For their own safety, they did time-opportunistic sampling, spending only about 10 minutes in each area of the cave.

“We would enter in batches, alternating whenever a member of the team would start having difficulty breathing,” Barrion-Dupo recalled, adding that, in the interest of efficiency, she kept her forceps and removed her gloves, opting to pick up specimens by hand. “We had to do our sampling quickly, and we were only able to check our specimens when we returned to the lab [at the UPLB Museum of Natural History].”

Soon, Barrion-Dupo heard back from the lab team. As it turns out, they noticed an uncommon trait in some of the specimens. “I was told, ‘Ma’am, some of these spiders have six eyes.'”

A six-eyed spider with a notorious bite

Most spider species have eight eyes. Their main pair of eyes, the principal eyes, enables them to see high-resolution color, albeit with a limited field of view. When used alongside their three pairs of secondary eyes, these arachnids achieve close to 360-degree vision. But a handful of spider families lack the main pair, and are thus six-eyed. The most noteworthy of these, perhaps, is the venomous Sicariidae, the family to which Loxosceles spiders—better known as recluse spiders—belong.

Over the years, Loxosceles spiders have developed an unfortunate, though not entirely unearned, reputation as being among the most dangerous spiders in the world. A bite from one of these 140-odd species can cause loxoscelism, which is the only proven spider-related cause of skin tissue death (dermonecrosis). Moreover, there is still no antivenom or treatment for Loxosceles bites.

However, based on numerous studies, most Loxosceles bites only result in mild skin irritation; in rare cases, they can cause severe pain, organ failure, bleeding, or death. Additionally, Loxosceles spiders aren’t known to be aggressive, biting only when threatened or pressed against skin. And even when they do bite, their fangs can’t penetrate clothing.

Also worth noting is the fact that while Loxosceles spiders have been recorded in every continent except Antarctica, they have never been found in the Philippines. At least, not until the Project 3 team’s fieldwork.

“When we flagged the six-eyed spiders, we wondered, ‘What kind of spiders could these be?’ Based on their physical characteristics, we were able to eliminate the possibilities. We suspected they could be Sicariidae, which led us to conduct further observation.”

Despite only having a few specimens available, DNA sequencing helped the researchers determine that they were Mediterranean recluse spiders (L. rufescens), confirming their early suspicions. When they returned to Kamantigue Cave in November that same year, they did an opportunistic population count. They spotted at least 153 individuals, which was enough for a viable population.

Their findings, which were published in February 2024, also gave Barrion-Dupo a bit of a shock, as she remembered that she had been collecting these spiders with unprotected hands. “I don’t recall being bitten during our fieldwork, which was a relief. But this still made me realize that in every instance, it’s important to be careful, because you can never truly anticipate what you would pick up in these caves.”

Stowaway spiders?

A hallmark of good science is when answering questions paves the way for even more questions. Barrion-Dupo and her team had already solved the mystery of this spider’s identity—but how did this non-native species get there, exactly?

For starters, compared to other spider species, Loxosceles spiders are total homebodies. They don’t engage in ballooning (releasing spider silk “parachutes” into the air, causing updrafts and electric fields to carry them and allowing them to literally ride the wind to new locations), and would much rather stay put in their habitat.

A 2018 study proposed a global model of distribution for L. rufescens, based on environmental factors like humidity and heat. Following these projections, the likeliest place in the Philippines where this species could land would be northern Luzon, specifically Ilocos Sur. But since the team found the spiders in Lobo—nearly 500 kilometers away from Ilocos Sur—this rules out the possibility that abiotic factors facilitated their spread. “This appears to be a case of human-mediated distribution,” said Barrion-Dupo.

Their molecular analysis traced the possible roots of Kamantigue Cave’s L. rufescens spiders to either India, Portugal, or Spain. Incidentally, locals confirmed that the specific area where Kamantigue Cave is located was part of an old trade route, a port accessible only via boat. Another possible explanation: The spiders may have hitched a ride in the bags of tourists or travelers from those countries. The cave’s dryness, darkness, and humidity made it the perfect new home for the spidery stowaways. Testing these theories requires further research, possibly even collaborations with historians who are knowledgeable about the area’s trade history.

With that said, the team’s discovery does more than contribute to the growing body of knowledge about spiders in the Philippines; it also has implications on policy, tourism, and even local science communication.

Cave of wonders—and dangers

Based on the classification system of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), Kamantigue Cave is a Class 1C cave, defined as a cave “with extremely hazardous conditions (e.g., bad air, unstable ceiling, presence of rock fall/breakdown… etc.).” While this takes into account the cave’s obvious geologic hazards, it does not factor in the possible biological dangers inside it, which can create risky situations for stubborn tourists or inadequately briefed scientists.

“It’s very important that we know what we’re looking at, and that we be careful in classifying which things are hazardous,” shared Barrion-Dupo, who mentioned that they are coordinating with the UPLB College of Public Affairs and Development to help them come up with a policy brief for DENR. “As scientists, we feel that it would be wrong not to voice out [our findings]. We must take the next step to change the policy.”

With that said, when it comes to nature, risk management goes both ways. Days after Barrion-Dupo’s team gathered the L. rufescens spiders, another group of researchers under the NICER-CAVES program, the Project 1 team, conducted a field survey of terrestrial vertebrate species in Kamantigue Cave and its surrounding karst areas. In their paper published in the peer-reviewed journal Laksambuhay, they suggested that the unnaturally robust presence of P. americana in the cave points to a “high level of disturbance” there; in other words, the non-native pests could have been brought there unknowingly by tourists.

“It is therefore recommended to implement and enforce regulations that control and limit human access to Kamantigue Cave to minimize disturbance to cave-dwelling species,” the Project 1 team wrote, stressing the need for “responsible tourism practices.”

Web of words

The first confirmed record of L. rufescens in the Philippines opens the floodgates to further scientific inquiry, which can only be satisfied with more fieldwork and research. But while it didn’t take too long for the researchers to confirm the Loxosceles spiders’ species, the journey toward getting their findings published was far from a breeze. When the Project 3 team initially submitted their paper, it underwent a “brutal” review and multiple revisions before ultimately getting rejected.

Undaunted—and more confident about their results, given the morphological and molecular analyses they had to do as part of the prior review process—they successfully submitted their paper to the Biodiversity Data Journal, a peer-reviewed publication with a “community-type” manuscript editing process that Barrion-Dupo described as “transparent” and “constructive.”

Another reason why the authors took a meticulous approach to preparing the manuscript for publication was the subject matter itself. For example, in the paper and even when communicating their findings to the public, the team made sure to mention the friendlier-sounding “violin spider”—a moniker derived from the violin-shaped mark on the spider’s back—as an alternative to “recluse,” a name that already has negative connotations. Even the use of the term “invasive” to describe the spiders underwent considerable scrutiny from the reviewers.

Jay Sebastian Fidelino, a research associate at the Biodiversity Research Laboratory of the University of the Philippines Diliman’s Institute of Biology, acknowledged that there is a PR aspect to consider in discussions about wildlife conservation, especially when it comes to less appealing species. “Using a less aggressive common name is a classic strategy, as some common names carry a lot of baggage, ‘recluse’ being a good example,” explained Fidelino, who was not part of the study. “I think it’s still valid and important to share the trickier common name, but maybe it’s best for it to not be the first thing people read.”

“We did our best not to invoke fear from the public,” recalled Barrion-Dupo. “When people hear about recluse spiders, they typically ask, ‘Are those deadly? Are those dangerous? Should we eradicate everything inside that cave?’ But this still needs to be reported; otherwise, people might continue to enter the cave, even if it’s restricted. And [the cave is] so close to the community that there’s no guarantee that people won’t come into contact with these spiders.

“That, and we were simply excited to report that this foreign spider was found in the Philippines for the first time.”

The taxing tasks of taxonomists

“While the front-facing aspect of taxonomy is the description of new species, the field is so much broader than that,” Fidelino shared. “Sometimes, we describe species that ‘suck,’ for lack of a better term. And as we see in this paper, these kinds of work can also have important implications on conservation.”

When the public thinks of taxonomists, the resulting discussion typically revolves around, and is limited to, scientific nomenclature and the discovery of new species. Some may even imagine taxonomists as walking repositories of scientific names who can easily identify a plant or animal with a single glance at a poorly lit smartphone photo. “We don’t just provide species identification unless we’re really sure about it,” Barrion-Dupo stressed. “I think that’s the mark of an expert: to search for and use the appropriate tools to identify the organism.”

According to Fidelino, the Project 3 team’s paper “showed a clear path from the ‘basics’ of taxonomy, in describing specimens of species, to its application, in the implications of the discovery on the potential impact of [species like L. rufescens] on other biodiversity and on human communities.”

Beyond simply attaching a scientific name to an unfamiliar species, taxonomists help lay the groundwork for humanity to better understand its relationship with the rest of the world. Some may question the practical, tangible value of their work. But it shouldn’t take any stretch of the imagination to realize that, as they crawl into narrow crevices and wade through bat excrement, taxonomists make it possible for rays of light to penetrate literal and figurative caverns full of the unknown.

To quote Barrion-Dupo in a statement she co-wrote with researcher Camille Faith D. Duran: “Much of what we discover now may not contribute to impacts that are measurable within our lifetime, but we do it, nonetheless. Someone must answer and cultivate curious questions like, ‘What’s this?'”—FS

The NICER-CAVES Program receives financial support from the Department of Science and Technology (DOST).

References

- https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2021.1760

- http://www.sci-news.com/paleontology/paradoryphoribius-chronocaribbeus-10139.html

- https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/930468

- https://www.popsci.com/science/rare-tardigrade-fossil/

- https://news.njit.edu/once-generation-tardigrade-fossil-discovery-reveals-new-species-16-million-year-old-amber

- https://www.iflscience.com/plants-and-animals/incredibly-rare-tardigrade-trapped-in-16millionyearold-amber-is-also-new-species/

Author: Mikael Angelo Francisco

Bitten by the science writing bug, Mikael has years of writing and editorial experience under his belt. As the editor-in-chief of FlipScience, Mikael has sworn to help make science more fun and interesting for geeky readers and casual audiences alike.