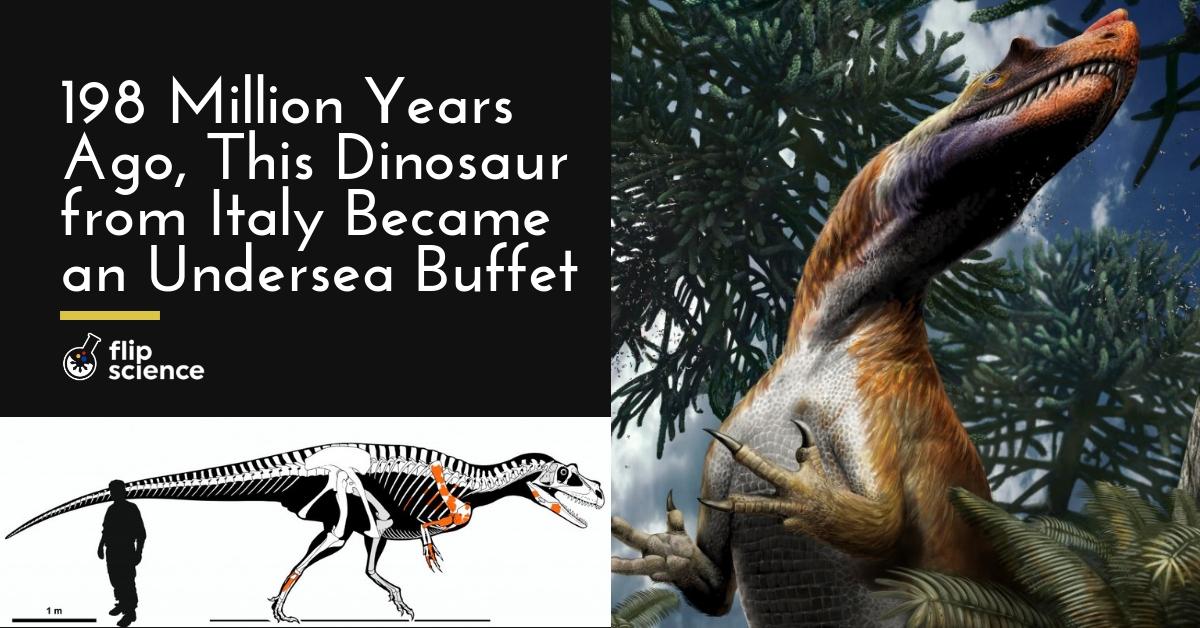

• Discovered by an amateur paleontologist in 1996, Saltriovenator zanellai is the first Jurassic-era dinosaur from Italy.

• The circumstances of its death were also remarkable — it’s one of the few dinosaurs whose remains show evidence of consumption by marine scavengers.

• This large predator also provides a vital clue in the mystery of bird wing evolution.

Approximately 198 million years ago, a large carnivorous dinosaur breathed its last. Somehow, its lifeless, one-ton body found its way into the sea, where it attracted all sorts of marine life. Prehistoric sharks, fish, and even invertebrates such as sea urchins and underwater worms dined on the massive, meaty carcass as it sank to the watery depths. There, its remains lay relatively undisturbed across the epochs, buried under what would eventually become the Italian Alps.

Even long after its death, however, Saltriovenator zanellai would continue to be part of a remarkable story — one that involves being blown to smithereens.

Prehistoric pride of Italy

Revealed to the world via the online research publishing platform PeerJ — the Journal of Life and Environmental Sciences, Saltriovenator is a monumental discovery, in more ways than one.

For starters, it is the first Jurassic-era dinosaur from Italy, and the country’s second-ever dinosaur. (The first was Scipionyx, an Early Cretaceous compsognathid discovered in 1981.)

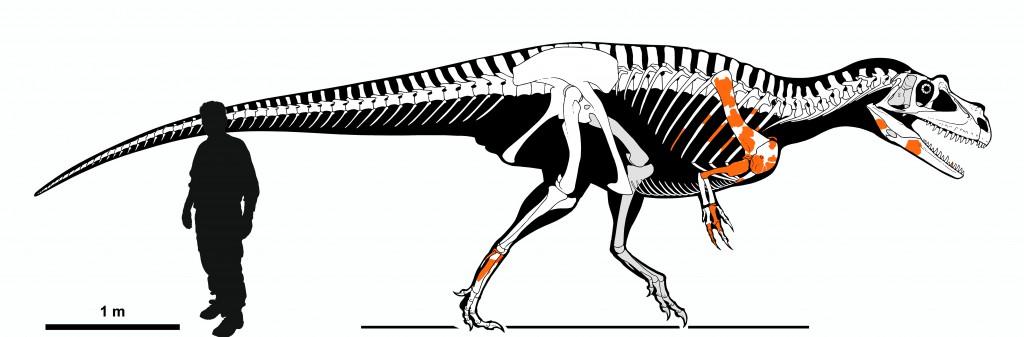

Saltriovenator also happens to be the oldest large-sized Jurassic predator, as well as the oldest known ceratosaurian. This is particularly significant, as Early Jurassic predatory dinosaurs are a rarity to begin with, especially gigantic ones. This particular specimen spanned about 7.5 meters (24.6 feet) in length, and had an 80-centimeter (2.5-foot) skull. It also had four-fingered forelimbs, with three fingers ending in sharp claws. However, researchers believe that this one wasn’t even full-grown yet.

Lead author Cristiano Dal Sasso called the find “absolutely unique.” The Milan Natural History Museum paleontologist added that most of the evidence of scavenging found on dinosaur bones were made by terrestrial animals, making Saltriovenator a truly one-of-a-kind case.

An explosive find

Amateur fossil hunter Angelo Zanella accidentally discovered Saltriovenator‘s remains in 1996. He found the bones in a quarry near Saltrio located about 50 miles (80 kilometers) northeast of Milan. Unfortunately, industrial workers had initially used dynamite in the quarry, inadvertently shattering the Jurassic carnivore’s bones.

“Not all fragments match, but many are adjacent and allow us to virtually reconstruct the shape of whole bones,” Dal Sasso explained. “To complete the puzzle we also used a 3-D printer: part of the left scapula was turned into the right one thanks to a ‘mirroring printing’ which gave us a more complete scapula.”

All in all Del Sasso and his team combined over 150 image files and examined 132 bone fragments, a dozen rib pieces, and 35 bones. The new species’ name borrows from its municipality of discovery, the Latin word for hunter (“venator”), and Zanella himself.

Winging it

Perhaps most importantly, though, a crucial clue in bird evolution appears to be in Saltriovenator‘s hands — literally.

Next to feathers, the development of bird hands is a topic that generates massive debate in the scientific community. Birds descended from theropods (two-legged carnivorous dinosaurs) such as Saltriovenator, and share numerous traits with their ancestors. Among these are hollow bones, feathers, and nest-building behavior. Scientists theorize that theropods evolved wings as an adaptation for catching prey.

On the subject of actual wing development, however, there are two popular theories. One traces wing evolution to the fusion of the first, second, and third fingers on theropods’ hands. Meanwhile, the other suggests that it was the second, third, and fourth fingers that merged.

Saltriovenator‘s discovery sheds new light on the million-year-old-mystery. The early theropod’s hand adds credence to the theory that they eventually lost their fourth fingers, leaving three to eventually form wings.

“The grasping hand of Saltriovenator fills a key gap in the theropod evolutionary tree: predatory dinosaurs progressively lost the pinky and ring fingers, and acquired the three-fingered hand which is the precursor of the avian wing,” according to co-author Andrea Cau.

And with these new findings, the key to determining how certain traits evolve may now be within scientists’ reach.

Cover photo: Marco Auditore; Davide Bonadonna

References

- http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/deadthings/2018/12/19/saltriovenator/

- https://edition.cnn.com/2018/12/19/world/italian-dinosaur-hands-bird-wings-study/index.html

- https://peerj.com/articles/5976/

- https://www.livescience.com/64348-italian-alps-dinosaur.html

- https://www.thewire.in/the-sciences/strange-big-dinosaur-predator-from-italy-was-given-a-burial-at-sea

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/12/181219075901.htm

Author: Mikael Angelo Francisco

Bitten by the science writing bug, Mikael has years of writing and editorial experience under his belt. As the editor-in-chief of FlipScience, Mikael has sworn to help make science more fun and interesting for geeky readers and casual audiences alike.