Have you ever wanted to become an astronaut? Have you ever fantasized about going out on a space adventure aboard the USS Enterprise or the Millenium Falcon? Ever wondered what it’s like to explore new worlds and experience new environments?

Well, I have. I grew up dreaming of becoming an astronaut, or living on the Moon and on Mars. Of floating in microgravity, or flying a spaceship in search of different worlds. All that, and so much more.

But, sadly, I was just a student — a simple, ordinary citizen, just like you. Realistically, what could I do?

Fast forward to December 2010. The Kepler mission was already in full swing. Tons of data were being churned out. Several exoplanets were already being found. Yet, scientists were still unsatisfied. How can you process all these data with so few people? They needed more help.

And so, through a citizen science platform called Zooniverse, Planet Hunters was born. Planet Hunters is an international collaborative project that sought the help of ordinary citizens to help analyze Kepler data. These were ordinary people from different disciplines — stock brokers, software engineers, policemen, retirees, students, etc. — with no formal astronomy education. All they had was the passion to learn and do astroscience.

That was then when I found my opportunity to realize my dream: I was going to hunt for exoplanets.

Snapshots of the first version of Planet Hunters .

Exo-what?

Exoplanets, or extrasolar planets, are planets located outside our own Solar System. They orbit stars other than our own Sun. Think Superman‘s Krypton, Avengers: Infinity War‘s Vormir, Star Wars‘ Tatooine, or Star Trek‘s Vulcan, but with one key difference: Exoplanets are the real deal.

Scientists have found almost 4,000 of these so far, many of which resemble our own planets. Some are gaseous (like Jupiter and Saturn) while others are rocky (like Earth and Mars).

However, some truly strange planets have also been found, such as hot Jupiters, ocean worlds, lava worlds, and ice giants. Remember Tatooine’s ‘double sun’ sunset?

Sunset on Tatooine, the fictional planet from ‘Star Wars’. Image: Disney/Lucasfilm

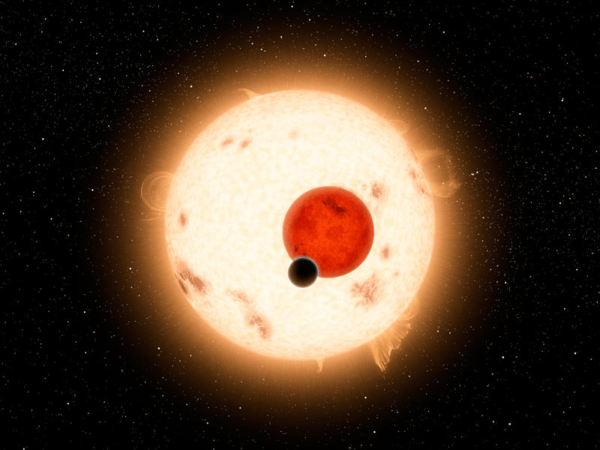

Planets like that are called circumbinary planets, and we actually found one: Kepler-16b.

Artist’s rendition of Kepler 16-b, Credits to NASA/JPL-Caltech

Nature didn’t stop there, though. Want a ‘quadruple sun’ sunset? Check out PH1b (Kepler-64b). Talk about life imitating art (and then some).

Artist’s rendition of PH1b (Kepler-64b). Image: Haven Giguere/Yale

Six years well spent

For six years, I actively volunteered, spending my free time looking at Kepler data for signs of activity. For signs of periodicity, of new worlds. Over the course of six years, I helped analyze thousands of stellar data, sifting through all that noise.

For six years, I helped discover new worlds.

I was fortunate enough to be acknowledged in the discovery of PH1b, the four-star system with a planet. I was also a co-author in a scientific paper published in The Astrophysical Journal in 2016 (as seen below).

Not only that, I learned a great deal about astronomy, while getting to know so many people and disciplines during those six years. Not bad for someone who didn’t have a degree in astronomy or astronautics, wouldn’t you agree?

TESS is your moment!

Sound amazing? It does! What’s even more amazing, though, is that it can happen to you, too!

Finding exoplanets is a tricky business. Keep in mind that these stars are so far away that we see them as tiny specks of light. How much more for these planets? Just more than 20 years ago, no one knew if these existed. No one could say if our Solar System was unique.

Then, in 1992, we had an answer. And another in 1995. Two decades later, we have thousands more — and we now have a number of ways for detecting exoplanets.

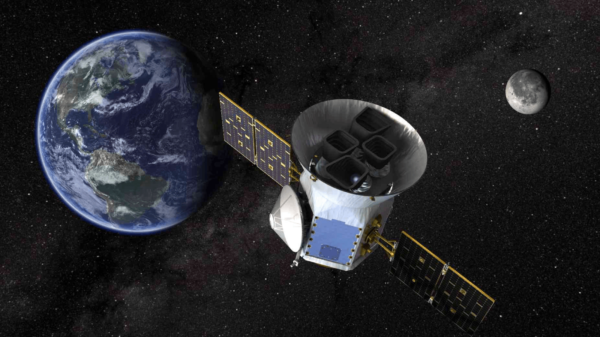

Just this week, Zooniverse relaunched its successful planet-hunting project, now called Planet Hunters TESS. Although Planet Hunters’ data source, Kepler, recently ended its run, TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) is now online. The mission is well underway for a two-year observation of about 200,000 nearby stars.

TESS. Image: NASA Goddard Spaceflight Center

Thanks to Planet Hunters, you can discover exoplanets within the comfort of your own home.

Planet Hunters 101

Radial velocity, gravitational microlensing, astrometry, direct imaging, and transit photometry all have their advantages and disadvantages. For example, radial velocity gives the planet’s mass while transit photometry gives its radius. Meanwhile, characterizing exoplanets — understanding their chemical composition, its atmosphere, and so on — is another story. It requires a combination of these detection methods and more.

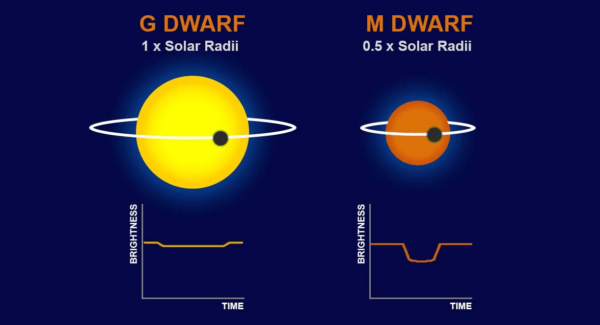

Planet Hunters uses transit photometry. Basically, Kepler and TESS stare at the stars and measure how their brightness changes over time. This data is called a lightcurve. When an exoplanet passes (or transits) in front of its parent star, the star momentarily dims and a dip is seen in the lightcurve. Sounds straightforward, right?

Image: Nora Eisner

Determining how big or small the transiting exoplanet is depends on how big the star is and how deep or shallow the dip is on the lightcurve. For example, as seen below, notice how the same transiting exoplanet results in two different dips for two different parent stars.

Image: Nora Eisner

Transit photometry also yields the exoplanet’s period. By measuring the elapsed time between successive dips, you can also determine how long it takes for that planet to complete one orbit. Or better yet, how long a year lasts in the world.

Aside from exoplanets, transit photometry has also resulted in the discovery of other cosmic phenomena, such as eclipsing binaries, supernovae, heartbeat stars, and even some weird ones like Tabby’s Star. (Which, mind you, was also discovered by Planet Hunters!)

Citizen science to the rescue!

You might be thinking: “Your explanations are clearly oversimplifications. Surely, this requires a lot of math and physics; clearly way above my head. Seems like a task meant for the professionals. How and why would you ever need a person like me?”

Yes, it is true that this is primarily a job for professional scientists. However, there’s always room to help.

Scientists from around the world have developed extremely efficient computer programs for processing tons of stellar data from the Kepler space telescope. (During its lifetime, it transmitted about 12 GB of data per month!) These machines are great in finding repeating signals but planetary systems are highly complex and real lightcurves are very noisy (as shown below).

Example lightcurve of a multi-planetary system.

Human brains, on the other hand, are excellent and highly efficient in detecting patterns in noisy data. We just need to know what to look for. Mind you, Planet Hunters yielded about 100 exoplanetary systems. This was how much the computers missed.

This is why we need you. This is where you come in.

Go and check out Planet Hunters TESS now at https://www.planethunters.org/, and help us discover the other wonders outer space has in store for us.

More to come

Still think your chances of finding an exoplanet are very slim?

Just think about this: Scientists predict there are at least 100 billion exoplanets in our Milky Way galaxy alone. That’s more planets than the number of Filipinos, even all the humans currently living! Not only that, more upcoming exoplanet missions are underway.

In other words, it’s not just Kepler and TESS — there are more to come.

Bored of just idly scrolling on social media? Why not help map the galaxy instead? Help us discover new worlds! All you need are an Internet connection, spare time, and, most importantly, passion.

Kapag may tiyaga, may planeta.

Happy hunting!

P.S. If astronomy is not your thing, you can also check out other Zooniverse science projects at https://www.zooniverse.org. These include literature, zoology, history, and meteorology, just to name a few. –MF

Cover photo: Pexels

References

- http://exoplanets.astro.yale.edu/science/citizenscience.php

- http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/0004-6256/151/6/159/meta#aj523306s1

- http://www.planetary.org/explore/space-topics/exoplanets/how-to-search-for-exoplanets.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exoplanet

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kepler_(spacecraft)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kepler-16b

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Methods_of_detecting_exoplanets

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milky_Way

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TESS

- https://www.planethunters.org/

- https://www.nasa.gov/content/kepler-64b-four-star-planet

- https://www.zooniverse.org

Author: Arvin Joseff Tan

Currently working on satellites, Arvin still finds time to explore his other interests in life: history, music, video games, and photography, just to name a few. When it comes to accumulating knowledge and learning, he has an insatiable thirst. He is one curious cat.